I was raised in a very conservative Christian family. I still believe in what Jesus taught, which I suppose still makes me a Christian, although the “conservative” part was permanently revoked when I got myself a tattoo for my 45th birthday. These days, however, I’m finding myself more and more reluctant to admit to being one. It pains me to be associated with what Christianity seems to have come to represent. There is such a huge conflict between what Jesus taught and how so many people who call themselves Christians actually live their lives that I find myself wanting to make up a new label to live under. Maybe it’s time for a revival of the term “Jesus People.” As I recall, there weren’t any special rules for being a Jesus People; they pretty much let anybody in. Probably even people with tattoos. This total lack of discrimination cost them a lot of respect, and perhaps even led to their downfall as an organized religion. But it did line up pretty well with one of the concepts I find lacking in far too many Christian circles these days: Grace.

Grace means you don’t have to be deserving. You can screw up, break the rules, fall flat on your face, wear plaid, shoot, you can even get tattoos, and still be okay. Jesus was big on grace. So much so that to make sure we really got the point that he was eliminating all the religious rules and rituals and replacing them with grace, he voluntarily took the death penalty, to prevent any possibility of our having to be held accountable for anything. He piled up all the nitpicky rules and requirements that had ever been created, and satisfied them all forever with one final payment in full. Then he replaced all those rules with a “new commandment” that he said would be how people would know who his real followers were. The new commandment was “love one another as I have loved you.”

Grace means you don’t have to be deserving. You can screw up, break the rules, fall flat on your face, wear plaid, shoot, you can even get tattoos, and still be okay. Jesus was big on grace. So much so that to make sure we really got the point that he was eliminating all the religious rules and rituals and replacing them with grace, he voluntarily took the death penalty, to prevent any possibility of our having to be held accountable for anything. He piled up all the nitpicky rules and requirements that had ever been created, and satisfied them all forever with one final payment in full. Then he replaced all those rules with a “new commandment” that he said would be how people would know who his real followers were. The new commandment was “love one another as I have loved you.”

He didn’t leave any room for doubt as to what that meant, either. Jesus loved by serving. He spent the majority of his time on health care, actually. He healed sick people, mostly people who didn’t even deserve it. He also purposely sought out and befriended society’s outcasts; adulterers, crooked tax collectors, prostitutes, even the despised Samaritans (the ancient Jewish equivalent of illegal aliens). Incidentally, he didn’t do those things for people because they believed in him. Mostly people believed in him because he treated them like they actually mattered.

Any kid who’s ever been to Sunday School can tell you this stuff. It’s no secret how Jesus loved people; it’s in all the Bible stories. He did it by giving everything he had to give, with no strings attached. Who did he love? Everybody, of course. But most pointedly, he loved the people society said didn’t deserve it. The less than. The people who had made stupid choices and screwed up their lives, or had the misfortune of being born to the wrong families, or had chosen unsavory occupations. In fact, he seemed to go out of his way to love those who least deserved it, those who were the most unlovable. And then he gave his life. In that act he demonstrated the ultimate extent of the new commandment he had given. He didn’t say “love one another as long as they deserve it but after you’ve made sure you can take care of yourself first and only if it’s not too hard for you.” He said “Love one another as I have loved you.” And he got down on his knees and washed smelly feet. He healed the sick, regardless of who they were, where they were from, or how they had lived their lives. He served, and loved, and held nothing in reserve; not even his own life.

That’s a hard act to follow. Some people are just downright hard to love. Some people totally don’t deserve to have anybody love them. Some people don’t even want to be loved. Maybe that’s why he made such a point of seeking out exactly those sorts of people to love, to underscore his intent, to make it crystal clear just what he meant when he exhorted his followers to do the same.

It’s real easy to talk about loving people, but it’s quite another thing to do it. So Christians have done what humans do when they are faced with a problem they can’t resolve, and taken refuge in a natural coping skill. We compartmentalize.

Compartmentalization is when we put things into different boxes in our brains. We can choose the boundaries of each box, and choose what sort of reality and expectations apply within those boundaries. Dividing things up like that simplifies things. Taken to extremes, it’s a coping skill that can become pathological. Children faced with a reality too terrifying to handle can sometimes compartmentalize themselves to such an extent that they create an entirely different persona in each box, each of them with their own subset of reality. This allows them to switch between personas based on which one’s reality and personality is best equipped to handle a given situation. It’s called dissociative identity disorder, otherwise known as “split personality.” It’s a protective strategy, and one we all use to some extent, just usually not to that extreme.

I find that Christians tend to build themselves a Sunday compartment. Since unlovable people don’t tend to show up at church on Sundays, they don’t have to exist in this box. Instead, we can just imagine all those people out there in the world who we’re supposed to love. They’re nameless, faceless people, preferably in far away places. It’s easy to imagine that we love them; we’re sure we would, if we knew them. Because in our imaginations they aren’t smelly or funny-looking or dishonest or undeserving. We can paint them as lovable in our imaginations, and then imagine ourselves loving them, and then to demonstrate our love, give money to someone closer to where they are, to use in serving them. It makes us feel benevolent and kind, and even Christ-like, and takes care of the whole “love one another” thing.

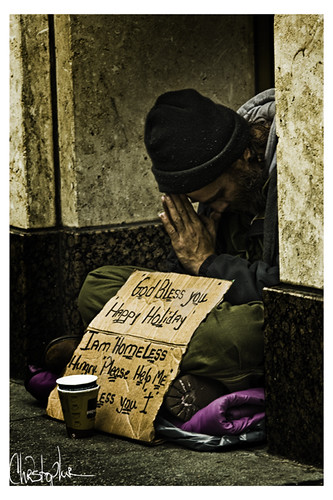

For the rest of the week, we move over into our day-to-day compartment, the one we’ve constructed for living in the real world. Since we’ve met the “love one another” requirement over there in the Sunday box, we don’t really have to worry about it too much in this box, other than to take credit for having accomplished it. In this compartment, real-world logic and values apply (you know, stuff Jesus didn’t have to deal with). The filthy ill-dressed man on the corner with a cardboard sign goes in this box. Unlike those imaginary people in faraway places, he’s not easy to love. For one thing, he smells bad. And what’s he doing on the corner asking for money instead of trying to get a job, like any responsible person would? Who does he think he is, asking for a free ride, and why should I give him money I’ve worked hard to earn, money I need to support myself and my own family? He needs to grow a backbone and work for it, like I have. In the day-to-day box, it’s a dog-eat-dog world, and only the strong survive. It’s really too bad for those who can’t make it; it’s not that I don’t feel bad for them, but you know, that’s just how life is. I’ve got to make sure I can provide for me and mine; I can’t afford to jeopardize my family‘s security for people who can’t even pull themselves up by their own bootstraps.

Being in a health care profession has opened my eyes to a lot of things I was able to conveniently overlook before. Working in psych means the reality I’m trying to come to terms with is one of the bleakest and harshest of all. I can’t paint appealing mental pictures of imaginary people to imagine myself loving, make a gesture of generosity to demonstrate that love, and then go back to my comfortable life and forget they exist for the rest of the week. I work on Sundays now, so I can’t even successfully keep the boundaries distinct between my Sunday compartment and my day-to-day compartment. The easy-to-love imaginary people have all faded and gone kind of fuzzy around the edges, overshadowed by the hard-to-love real people who have crowded in. This has forced me to face what love, the way Jesus practiced it, really means. It’s hard. I’m not even sure it’s entirely humanly possible. But that word “commandment” really just doesn’t leave a lot of wiggle room.

I guess I’ve made some progress. I know this because of the current health care debate. I see what my fellow Christians are saying, and am shocked and appalled that people who claim a spiritual belief system predicated on loving and serving their fellow man could be so openly heartless and uncaring. Especially since some of the ones saying the things that sound so harsh and calloused are people I love and respect. It’s jarring, and to tell you the truth, it’s got me wanting to build a whole new set of compartments to hide myself away in.

I am ashamed. I am ashamed that we’ve forgotten the truth. I am ashamed that we who have been so blessed can be so arrogant as to think, somehow, that it’s because we actually deserve to have better lives than those around us who are suffering. And I am ashamed because I remember when I have hidden inside my own Sunday box, selectively applying my beliefs to the world only where it wasn’t too painful and difficult, and turning a blind eye on the rest.

I recently read Matthew 25, for like the bazillionth time, and was stunned to realize that in all those previous times of reading it, I had never fully comprehended what it actually says. I guess that’s because the Sunday box tends to also serve as the Bible-reading box. With the walls of my Sunday box all falling apart the way they are now, some of the stuff Jesus said in the sermon he preached in that chapter has suddenly taken on new depths of meaning. His words show just how seriously he meant that command to love one another, and he describes quite plainly how we will end up being judged by whether we took it to heart:

Then he will say to those on his left, “Depart from me, you who are cursed…For I was hungry and you gave me nothing to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not invite me in, I needed clothes and you did not clothe me, I was sick and in prison and you did not look after me…I tell you the truth, whatever you did not do for one of the least of these, you did not do for me.” (Matthew 25:41-45, NIV)

Take a look. The single criterion that will ultimately determine whether we have accomplished what is expected of us as Christians is whether or not we have loved our fellow humans as Jesus loved us. Failure to do so seems to be the one thing that can finally render someone unlovable, too. “You who are cursed” is pretty harsh, from someone who can love even the most miserable of screwups. I find that pretty sobering.

John 14:6 is worth a look, too. That’s where Jesus said (KJV), “I am the way, the truth, and the life. No man cometh unto the father but by me.” I was always taught that what Jesus meant there was that the only way to God was by believing in Jesus. But you know, believing’s easy. If that’s all he wanted, he could have just done a few miracles for a few deserving folk, and left out all the hard stuff like washing feet and loving publicans and sinners and Samaritans. Especially in light of how badly those things hurt his reputation with the religious folks. Shoot, if he’d have worked a little harder to keep his reputation clean, the priests and rabbis might even have accepted him as the Messiah.

But back to my point: I’m thinking now that Jesus expected a little more of us than just believing in his existence. He wanted us to strive to become what he represented — the embodiment of love, the servant of mankind. That’s why he went on, a few verses later, to specify that believing wasn’t the whole ballgame: “He that believeth on me, the works that I do shall he do also…” That word “shall” indicates a requirement, not a suggestion. Ask any lawyer.

People are sick and dying. Not just people conveniently off in some far-away land we’ll never see. They’re dying right here, in our own country. In our own cities and towns. And we’re letting them, while we quibble heartlessly over just who deserves to be taken care of when they’re sick, and who, by golly, is NOT going to help pay for it. I am stunned at the shallowness of it all.

I was sick…and you did not look after me…

…I tell you the truth, whatever you did not do for one of the least of these, you did not do for me.

What Would Jesus Do?

12 Responses to Dissociative Society Disorder